Lessons Written in Mud: Why We Can’t Drain the Swamp

Reflecting on the mistakes of past societies and the future of wetland conservation.

Last week marked the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. Countless case studies undertaken in the years since have pinpointed catastrophic levee failure in New Orleans, Louisiana as a major contributor to the devastation, loss of life, and flooding from the storm. As one article explains, “Designed to protect the city from a surge of at least 11.2 feet above sea level, the walls failed with a maximum surge of 10.5 feet—thus, before their design criteria were exceeded. It takes another two days for the floodwaters inside the city and in Lake Pontchartrain to equalize to about three feet above sea level. This leaves the average home in six to nine feet of standing water.” But the other failure, written in mud, was the destruction of swampland that had begun tens, even hundreds of years earlier.

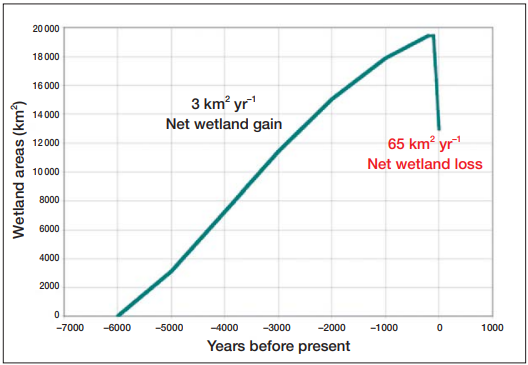

French colonizers began strengthening the Mississippi’s banks in the 1700s. The work was grueling - people died in early attempts to control the river. But these first levees often couldn’t hold up during floods, and they were easily damaged. As federal funds supported the deepening of the river to ease navigation and levees became more extensive at the turn of the 20th century, wetlands stopped gaining area. Their slow natural expansion rapidly turned into a freefall of land loss. Displacement and damage brought on by the Katrina disaster refocused the attention of politicians, scientists, and communities across the nation on the reality of our coasts.

National Wildlife Federation’s senior communications manager shared, “Before, wetlands were dismissed as ‘swamps’ standing in the way of progress. Now they’re widely recognized as life-saving infrastructure—just as critical as levees and floodwalls—and as part of the cultural and ecological fabric that makes coastal Louisiana unlike anywhere else.” Though healthy wetlands wouldn’t have stopped the storm, their functionality as natural hurricane protection is impossible to argue. Engineers have known for decades that each mile of wetland protects against 0.37 feet of storm surge. More extensive wetlands directly protect lives and property.

Now that wetland protections under the United States’ Clean Water Act are under threat, it’s important to restate why we can’t “drain the swamp”. The current administration seeks to redefine protected wetlands as sites with surface water during the entire wet season that are connected to a water body that also flows throughout the duration of the wet season. The stipulation about connection to another waterbody has been a loophole for developers and others to destroy inland wetlands since the 2023 Supreme Court decision, Sackett v. EPA.

That ruling stripped protections from inland wetlands that fed pollinators, peat swamps disconnected from their streams (scroll to “science highlights” after clicking link), wetlands surrounded by levees, groundwater-fed prairie potholes and karsts, precipitation-fed bogs, and ephemeral ponds. But the caveat of continuous surface water throughout the wet season would exclude even more ecological havens with natural variability in water level - which is actually beneficial for plants, soil, and bacteria because it promotes root respiration.

Wetland functionality can’t be reduced to the number of days with surface water coverage - groundwater, precipitation, and surface water all contribute to soil saturation levels, and there are entire fields of science (e.g., hydrological monitoring, remote sensing, numerical modeling) dedicated to understanding every nuance of this relationship. Seasons can’t be simplified to “wet” or “dry” in a world where spring is coming earlier, fall is happening later, and winter is disappearing altogether. Most importantly, humanity cannot continue down the course of environmental destruction without expecting consequences. These are the lessons that have been written in mud.

Hot off the Peat

Upstate New York is a freshwater fisher’s paradise that deserves protection. Check out this brief article featuring photos of pumpkinseed, rock bass, and largemouth bass.

Science-based nonprofit CarbonBrief fights solar misinformation with facts. Their new factsheet highlights fun facts about the technology behind two-thirds of global electricity capacity. For instance, did you know that coal produces two to three orders of magnitude more waste than photovoltaics? Additionally, solar panel power output and lifespan continues to increase with time. Knowing the truth is important to combat right-wing organizations attempting to ban this low-cost energy source worldwide.

Yosemite and Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks employees unionized! Almost all permanent and seasonal employees chose the National Federation of Federal Employees to represent them and have protections from illegal firings, low pay, unacceptable housing conditions, slashed budgets, and workplace safety violations. These changes are also expected to improve visitor experience and help continue the preservation of public lands.

Drought stress can change the chemistry of a forest floor. Scientists tested leaf litter from a climate manipulation experiment where rain was redirected from one glasshouse to a sprinkler system in other, creating drier or wetter conditions in the plants and soil below. Rainfall didn’t just influence the chemical composition of plant leaves as they grew - it also had an impact on their decomposition. Specifically, leaves from drier treatments took longer to decompose, even in wet soils, due to more alkyl compounds and lignin. These results illustrate the long-term effects of drought stress.

Deforestation is taking peoples’ lives through heat-related illness. Residents of Southeast Asia, tropical Africa, and Central & South America have suffered the consequences of clear-cutting for plantation farming, which removes shade, reduces rainfall, and boosts the probability of wildfire. Researchers quantified the exact numbers to key people in on the seriousness of this issue: 28,330 preventable deaths each year from 2001 to 2020, 345 million people impacted, and 3° Celsius of excess heat.